Weekly Outlook

The Swiss shocker, the British turn, the Japanese puzzle

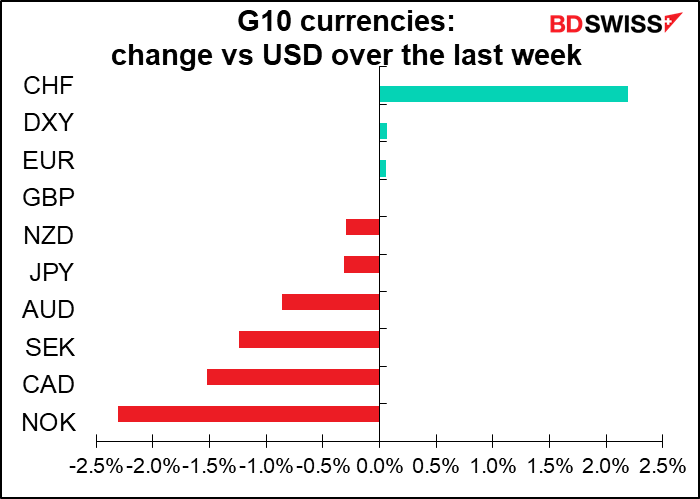

The title of my column last week was “Is 50 the new 25?” Apparently so – even the Swiss National Bank (SNB) hiked by 50 bps, the first change in its policy rate since 2015.

While Goldman Sachs did flag the possibility of a change, this was hardly a consensus view. Out of the 20 forecasts on Bloomberg, only one – Citigroup – was forecasting a change, and even that was only 25 bps. Even GS itself was not forecasting a change! So this really took the market by surprise (he says, trying to explain why he got it wrong too).

Furthermore, the SNB changed its view on CHF, which it has said for years now is “highly valued.” SNB President Jordan said,

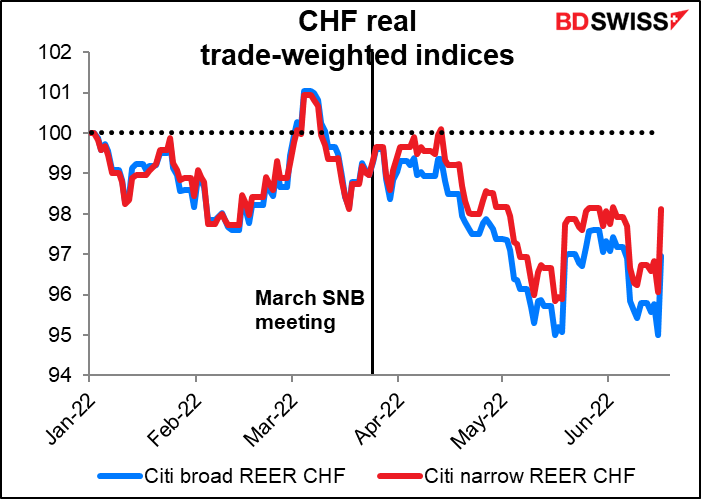

Since the last monetary policy assessment, the development of the Swiss franc exchange rate has also contributed to the rise in inflation. The Swiss franc has depreciated in trade-weighted terms, despite the higher inflation abroad. Thus the inflation imported from abroad into Switzerland has increased. Another consequence of this depreciation coupled with significantly higher inflation abroad is that the Swiss franc is no longer highly valued.

I have to say, I disagree with President Jordan. On the one hand it is true that the real (= inflation-adjusted) value of the CHF has fallen since the March meeting.

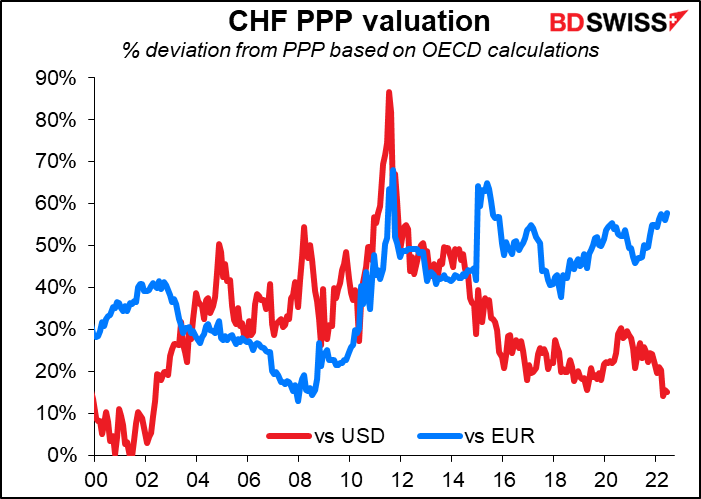

On the other hand…according to the OECD’s method of calculating purchasing power parity, CHF is still “highly valued” vs EUR = over 50% overvalued, in fact.

According to this methodology, only NOK is anywhere near fairly valued vs CHF.

To make matters worse, the SNB changed its one-way intervention policy to be double-sided. Previously they said that the SNB “is willing to intervene in the foreign exchange market as necessary, in order to counter upward pressure on the Swiss franc.” Now their official statement reads, “To ensure appropriate monetary conditions, the SNB is also willing to be active in the foreign exchange market as necessary.” That’s a bit vague, no? President Jordan clarified what this means: “If there were to be an excessive appreciation of the Swiss franc, we would be prepared to purchase foreign currency. If the Swiss franc were to weaken, however, we would also consider selling foreign currency.” That’s a huge change for one of the countries that has been the most active in the world in intervening to keep its currency from appreciating.

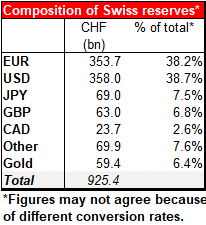

Switzerland has CHF 925bn ($952bn) in reserves, the third largest foreign exchange reserves in the world, after China ($3.188tn) and Japan ($!.209tn). Bear in mind that China’s annual GDP is $19.9tn, Japan is $4.9tn, and tiny Switzerland is $842bn. In other words, Switzerland has more than one year’s worth of GDP stored up in its FX reserves. It has considerable firepower if it wants to keep its currency from depreciating. Furthermore, the SNB is one of the few central banks that owns equities as well as bonds. The risk here is that it may sell some of its its $177.3bn in US equities.

However, I’m not too worried about that because I can scarcely imagine a situation in which the SNB would think its currency is getting too weak.

Meanwhile, the Bank of England voted for a 25 bps hike as was expected, but three of the nine members of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted for a 50 bps hike. In addition, the tone of the forward guidance was much, much harsher. Last month they said “most members of the Committee judge that some degree of further tightening in monetary policy may still be appropriate in the coming months. There are risks on both sides of that judgement…”

No such disagreement or hedging of bets this time! No “most members” or “may still be appropriate…” They said quite clearly:

The MPC will take the actions necessary to return inflation to the 2% target sustainably in the medium term, in line with its remit. The scale, pace and timing of any further increases in Bank Rate will reflect the Committee’s assessment of the economic outlook and inflationary pressures. The Committee will be particularly alert to indications of more persistent inflationary pressures, and will if necessary act forcefully in response.

“Act forcefully” probably means “hike by 50 bps.”

The problem is, what is the purpose of raising interest rates? It’s to slow the economy. But the UK economy is already slowing and the OECD forecasts that the country’s economy will stagnate next year. Against that background, one has to ask what good it will do to slow the economy further. The MPC argued that “not all of the excess inflation can be attributed to global events.” “There has also been a role for interactions with domestic factors, including the tight labour market and the pricing strategies of firms,” they said. So they need to “loosen up” the labor market (= cause unemployment to rise) and above all, convince companies that inflation isn’t going to stay like this so they needn’t raise their prices all that much. It will be interesting to see if they’re successful.

In contrast with the Swiss shocker and the Bank of England hawkish turn, the Bank of Japan simply kept to its well-worn path. Its only concession to the change in the global environment was a to insert a small comment about watching the exchange rate into their statement following the meeting (“…it is necessary to pay due attention to developments in financial and foreign exchange markets and their impact on Japan’s economic activity and prices.”).

That may have been a sign that they’re worried about the currency, but so far there’s no sign that they’re considering doing anything because of these concerns. On the contrary, they even retained their easing bias (The BoJ “will not hesitate to take additional easing measures if necessary; it also expects short- and long-term policy interest rates to remain at their present or lower levels.”) And as usual there was only one dissent, from Mr. Kataoka, who as always wanted to loosen policy further. So while the Policy Board expressed concern about the yen’s weakness, members unanimously decided not to change the policy that’s causing it.

Nonetheless the yen didn’t weaken much if at all, which implies that the result was pretty much as expected.

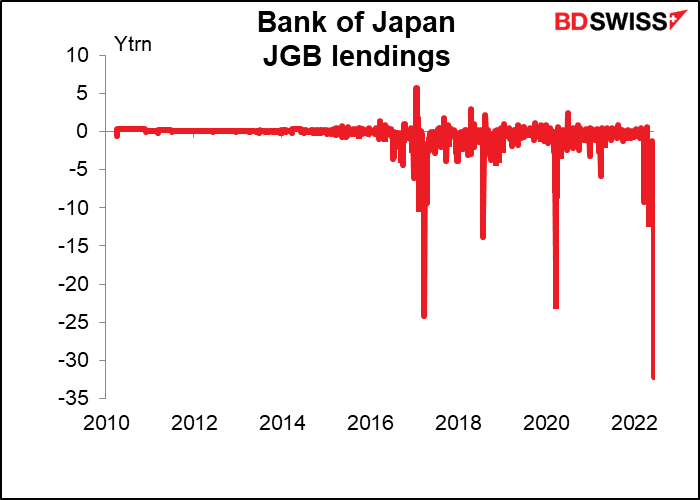

Meanwhile it was a very expensive week for the BoJ after it bought some JPY 9.6tn worth of Japanese government bonds (JGBs), or some USD 72bn, to keep the yield on the 10-year JGB under the 0.25% ceiling that the Bank has set with its “yield curve control” (YCC) policy. That’s more than what the Fed and European Central Bank (ECB) were buying per month last year for economies that are much much larger (GDP: US, $25.3tn; Eurozone, $14.5tn; Japan, $4.9tn). Japan’s QE this week has been running more than 20x the pace of the Fed’s QE in 2021, adjusted for the size of the economy.

Can they continue to intervene like this? Of course the central bank can create money and buy assets without limit, but if it continues like this it will hoover up all the JGBs and leave the market stranded, which is no good. The BoJ is having to lend an unprecedented JPY 32.2tn ($240bn) in bonds to the market to keep it functioning.

At the press conference following the meeting, BoJ Gov. Kuroda denied that any change was likely. He said he doesn’t believe the sustainability of the YCC policy is threatened and doesn’t believe a further review of the policy is necessary.

Of course everyone remembers that back in 2015, the SNB described its EUR/CHF floor as the “cornerstone” of its monetary policy only days before removing it without warning. “If you decide to exit such a policy, you have to take the markets by surprise,” Jordan said at the time. That’s what the SNB did this week too; will it be what the BoJ does sooner or later?

I agree that they’ll have to change policy at some point, but probably not the same way as the SNB. The Japanese authorities don’t like surprises, which they worry could cause the dreaded “confusion in the marketplace.” So we’ll probably get some hints in the Nikkei newspaper first.

Next week: Preliminary PMIs, Canada & Japan inflation

After all the Sturm und Drang of this week, next week is much quieter. There are no major central bank meetings, although the market will watch Fed Chair Powell testify to Congress Wednesday and Thursday. Monday is a federal holiday in the US (Juneteenth). Usually there are three inflation figures out during the week but we already had the UK inflation figures, so only two – Canada and Japan. And even at that, the Japanese figure isn’t that interesting because it largely followed the Tokyo CPI, which comes out about two weeks earlier.

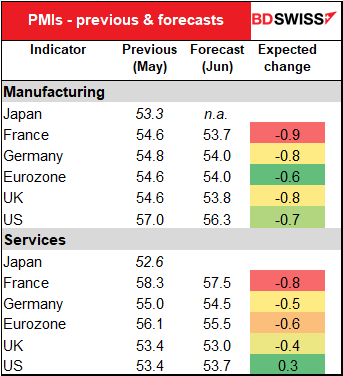

The main point of interest during the week will be the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major industrial economies. They’re expected to be uniformly lower, in line with the slowdown seen in many economies recently. This could dampen investors’ appetite for risky assets, such as stocks, and drag down AUD.

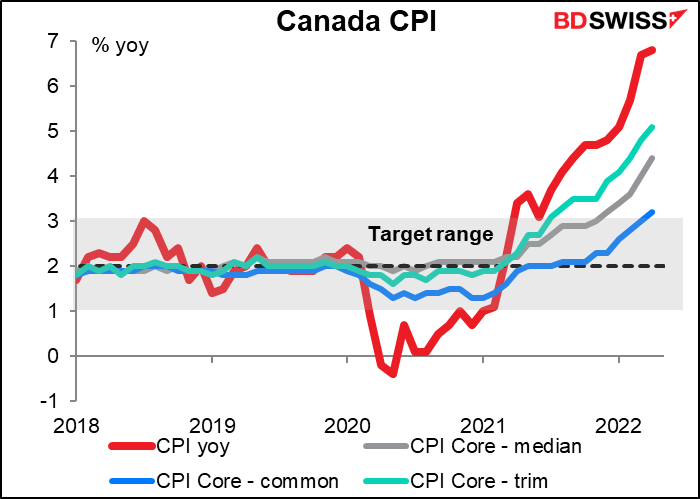

There aren’t any forecasts available yet for Canada’s CPI (Wednesday) but here’s a graph of the latest data we do have. Even all three core measures are above the Bank of Canada’s 1%-3% target range. They’ll have to do something about this.

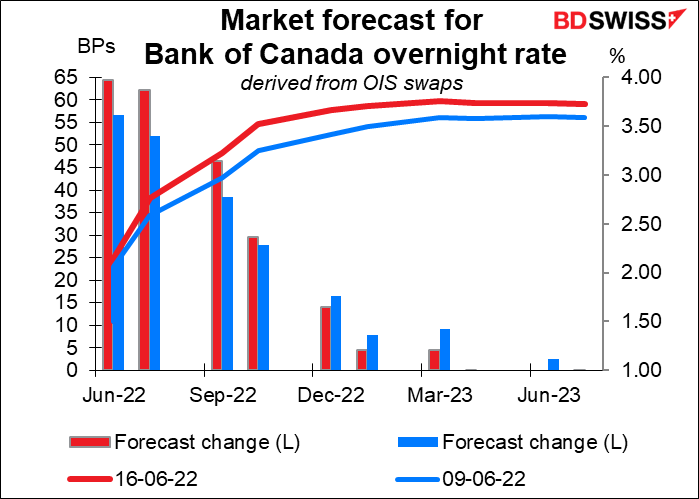

The market has been increasing its estimate for near-term Bank of Canada tightening recently.

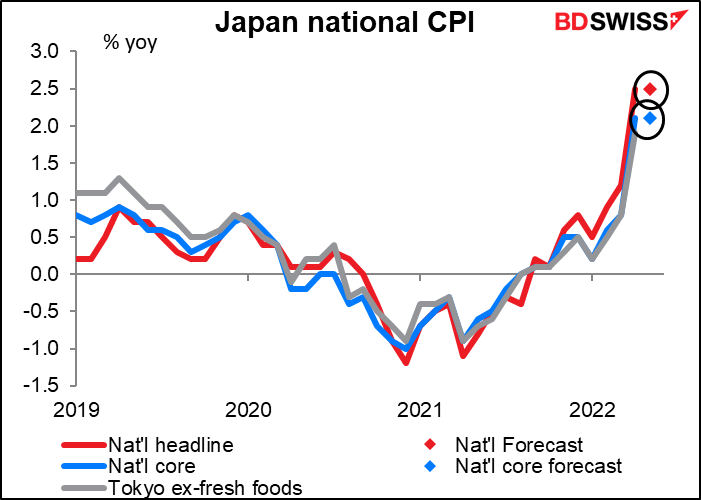

Japan’s national CPI will be released Friday, but a) the year-on-year rate of inflation is expected to be unchanged, b) it’s forecast to be pretty much the same as the already-released Tokyo CPI, and c) nobody cares anyway because we just heard from the Bank of Japan that they’re not yet even “thinking about thinking about” raising rates any time soon.

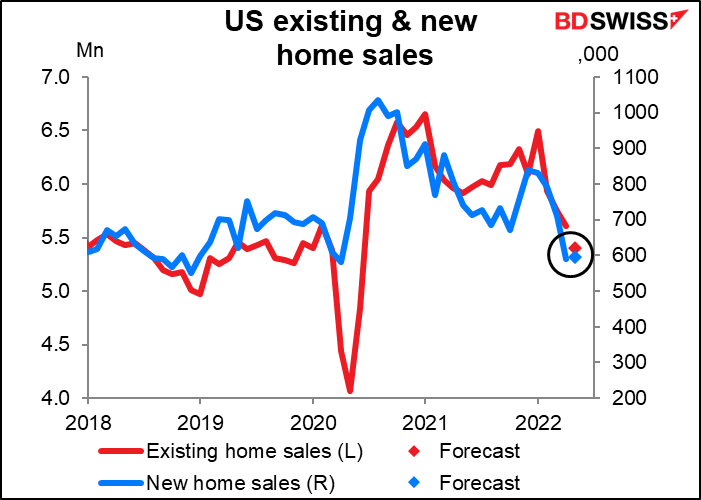

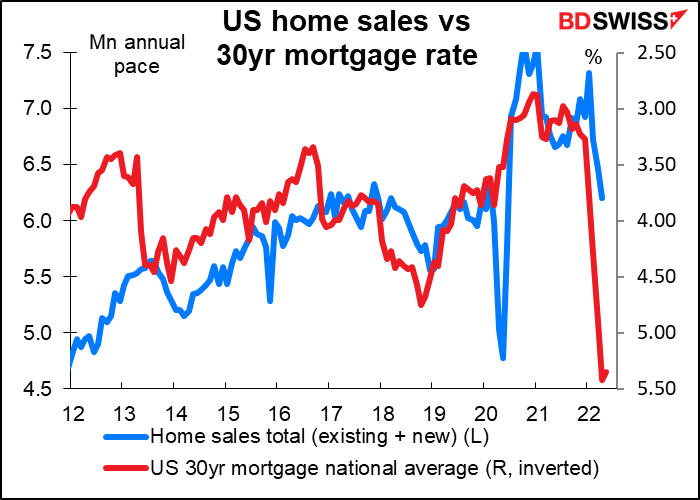

There are precious few US indicators out during the week. About the only important ones are existing home sales (Tue) and new home sales (Fri). The housing market is a bellwether for the impact that the Fed is having on the economy, because it’s probably the most important interest-rate sensitive sector (along with auto sales, perhaps). Given the big increase in mortgage rates recently and the plunge in housing starts and building permits announced Thursday, it would be no surprise to see home sales plunge too.

As is, existing home sales are expected to be down 3.7% mom but new home sales are forecast to be up 0.7%. We’ll see. These forecasts are subject to change without notice.